Danish bikes have global reputations, but it is in the cargo bike niche market that things are really moving forward for Danish Design.

The Nihola is the cargo bike with the most awards and the best reputation. www.nihola.info. Lightweight and roomy, it also comes in varying sizes.

It is this bike that has enjoyed a massive export market and it can be seen all over Europe.

The Sorte Jernhest [Translation: Black Iron Horse] is a classic. The design is radically different and, despite it's weight, it is a pleasure to ride.

The Cash & Carry bike is the cheapest on the market. Doesn't make it great, however. But you see many of them on the streets.

The Christiania bike [not pictured] basically started it all on the Danish market. It is much heavier than the present competition but it remains a staple on the streets of Copenhagen. It's a legend in it's own time.

Then you have the Triobike. A 3 in 1 solution to your urban, European needs. A bike on it's own, a stroller and a cargo bike.

Our bike culture has come a long way over the past century and a bit. Back in the day, in the late 1800's, riding bikes was not considered cool. Cyclists were spit on and heckled [kind of like riding in American cities in 2007...] because cycling was viewed as a disturbance.

Indeed, cycling in some Danish cities was illegal. The town of Slagelse, for example, first legalised cycling in 1885.

Since then, however, we've gone from strength to strength, creating one of the world's leading bike nations and the world's foremost bike city - Copenhagen.

Above: The train station in Odense, Denmark in the 1940's.

Note the bike racks on the right.

The same as these ones in a Copenhagen backyard.

Above: Manned bike parking in Odense, Denmark during WW2.

An association that battled unemployment set up safe bike parking facilities so you could leave you bike behind for a cheap price - 25 øre - and not worry about your tyres getting stolen. Rubber was rationed.

Another manned bike parking area in Odense, Denmark in September 1952.

You paid the man in the little wooden shed.

[Archive photos from the newspaper 'Fyens Stiftstidende' and the city archives]

Above: You always meet people you know when commuting by bike. One distinct advantage over automotive pursuits.

The country's second largest party - The Social Democrats - have announced a plan for improving Denmark's status as a leading cycle nation.

"The bike is a multi-dimensional problem solver", says Rasmus Prehn, the Social Democrats bicycle spokesman. [Yes, our political parties actually have an MP who is desginated as bike spokesman/woman]

The party aims to invest 1 billion Danish kroner - [135 million euros / 200 million dollars] - over ten years in our already well-established bike culture.

The party points to several studies, including a Norwegian one that shows that national investment in cycling infrastructure and culture will earn the state three times as much as their intial investment. This profit comes from less money spent on roads and less money spent on health issues - the more the people ride, the less they suffer from "The American Illness" - obesity - and other lifestyle illnesses like diabetes 2 and heart disease.

It's a detailed document they've written but it contains several highlights:

-Aiming to brand Denmark as the world's leading bicycling nation and as the nation in the world that has done the most for advocating bicycling.

- Establishing bike 'motorways'.

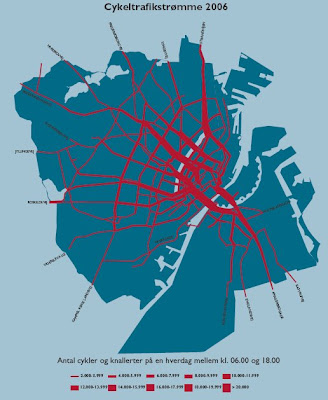

In Copenhagen there are roads that have excessive amounts of bikes. Over 20,000 bikes between 06:00 and 24:00. Creating dedicated bike motorways will make it easier and quicker to ride through the city.

- Better parking facilites for bikes in the big cities and for commuters.

- More and better bike lanes/paths.

- Making it free to take bikes on trains and busses.

At the moment there is a fee for taking bikes on trains - 2 dollars in Copenhagen.

- Service stations at busy train and bus stations.

Many people don't ride their bikes because they're not fixed. Establishing service centres wiill give them the chance to have their bikes repaired while they're at work or school.

- Increased safety in traffic.

All very interesting, all very promising. It is, however, a political party so let's see what they actually do with the proposal.

All in all it shows how important the bike is for Denmark and Copenhagen.

Sources: Politiken.dk [in Danish] & Social Democrats [in Danish]

The truth is finally out...

"Last year a survey found Denmark to be the happiest place in the world, based on standards of health, welfare, and education. Now the country's capital is ranked the second most liveable city in the world by the esteemed Monocle magazine .

When it comes to quality of life, Copenhagen is pretty hard to beat. In fact, only Munich does better in Monocle magazine's recently published survey of the world's most liveable cities.

To sum up the spirit of the Danish capital, Monocle writer Stuart Husband quotes the advertising slogan "there's something modern in the state of Denmark", which in his view "encapsulates Copenhagen's current mood of creative maelstrom and youthful dynamism rather adroitly". Contributing to this sense of dynamic modernity is the new wave of architects, designers and chefs - combined with "some joined-up thinking by city officials" - which has seen Copenhagen reborn with "a bullish mood".

Monocle lists a number of 'metrics' that contribute to Copenhagen's high placing. They include public transport, the extension at the city's airport, the freshly-minted statement buildings lining the harbour, a well developed bicycle network , the café culture, the neither harried nor sleepy pace and design and creativity."

Monocle's Top Ten liveable cities

1. Munich

2. Copenhagen

3. Zürich

4. Tokyo

5. Vienna

6. Helsinki

7. Sydney

8. Stockholm

9. Honolulu

10. Madrid

[From VisitCopenhagen Press Centre]

A little mood piece about cycling in Copenhagen.

These are my bikes lights. I also have a fixed red light on the back of my bike. In most Danish homes and bags you'll find a ragtag collection of bike lights. Many people are installing fixed lights that work when you ride but are otherwise off.

I use the ones above. They're cheap, they are legally within the law regarding strength and visibility. And, if they break, I just buy new ones for 35 kroner - roughly 7 dollars.

The Danish Traffic Law has strict rules for bike lights. See how they compare with your laws at home:

From the Danish Traffic Law [Færdselsloven]:

Time frame

All bike must have lights on from sunset to sunrise as well as in weather with restricted visibility, for example fog and heavy snow.

Bike lights on normal bikes

A two-wheel bike must be equipped with at least one front light and one back light.

Bike lights on bikes with more than two wheels

On bikes with more than two wheels there must be at least one front light which must sit no higher than 50cm from the bikes farthest left point.

If the bike is more than 1 metre wide there must be at least two back lights.

The back lights must sit no higher than 40 cm from the bottom edge and with at least 60 cm between them. If the bike isn't over 1 metre wide, one back light is sufficient and it must sit in the middle of the bike or to the left of the middle.

Mounting the lights

The lights must be placed on the bike and not on the cyclist. Bike lights in back pockets or on the leg must not be used alone but you're welcome to use them as a supplement to the ones mounted on the bike.

Specifications

A bike light must be clearly visible from a distance of at least 300 metres without being blinding. The light must also be visible from the side.

The front light must be white, blueish or yellowish.

Front lights that are white og blueish can flash at least 120 times a minute.

Yellowish front lights must not blink.

Back lights must be red and a back light may flash but it must be at least 120 times a minute.

Bikeshop Rainbow, originally uploaded by [Zakkaliciousness].

Anyone who has seen my Flickr photostream or my blogs may have gathered that we have a lot of bikes and pure bicycle culture in Denmark... :-)

Here are some colourful models on sale outside a bikeshop. We call these models "Grandma bikes", for ladies.

Oddly it's taken a century for bike manufacturers to start producing bikes in colours other than black or brown. Nice to see more colours on the streets. You get that old school cool feeling with the pleasure of riding a spanking new bike.

The Copenhagen City City Council had the consultancy company Trafitec to rate the societal and health aspects of our bicycle culture. The figures are specific to Copenhagen, based on our current levels of health and welfare, but the results and stats are fascinating.

Just the facts:

Physically active people live ca. 5 years longer than physically inactive.

Physically inactive persons suffer on average for four more years from lengthy illnesses.

Cycling has the same effect on health as other types of excercise. Four hours of cycling a week, or roughly 10 km a day is a fitting level - luckily this is the average bike usage in Copenhagen - back and forth to work and running errands.

The study from Trafitec shows that 1 extra cycle kilometre produces, on average, 5 kroner [1 dollar] in health and production bonus for society. Increased cycling levels in Copenhagen therefore has a great potential for improving our health levels.

Here are two scenarios that illustrate the positive connection between cycling, health and economy.

1. If Copenhageners rode 10% more kilometres each year:

(the population is 1.7 million)

-This would be an increase of 41 million extra cycling kilometres each year.

- The health system would save 59 million kroner per year. - We would save 155 million kroner in lost production manhours (due to illness)

- There would be 57,000 fewer sick days in the workplace each year. That would be a reduction of 3.3%.

- 61,000 extra life years

- 46,000 fewer years with lenghty illnesses.

2. One extra kilometre of bike lanes on a road:

Building bike lanes on streets with an average of 2,500 bikes and 10,000 cars each day would bring 18-20% more bikes on the stretch of road.

Including a drop of 9-10% in the number of cars and 9-10% fewer accidents and injury.

- A saving of 246,000 kroner in the health sector.

- A saving of of 643,000 kroner in lost production.

- A collective fall in health, production and accident costs each year totalling 633,000 kroner.-

- The extra kilometre would give 170,000 more cycle kilometres each years.

All that from one extra kilometre of bike lane.

Okay, okay, maybe all these stats are a bit boring... but I find them interesting. But remember you can always pop over to the Cycle Chic for a little respite from the stats.

The map of Greater Copenhagen is from the Bicycle Audit 2006 [Cykelregnskab 2006] from Copenhagen City Council. It shows how many bikes are on the bike lanes and streets each day between 06:00 and 18:00. The thickest red lines show that over 20,000 bikes are using the infrastructure on those routes.

Indeed, rush hour on bikes is something you see on weekdays. 100+ bikes lined up at traffic lights on the bike lanes, waiting to move towards or away from work or school.

For reference, there are over 500,000 cyclists on the streets every day. 36% of 1.7 million citizens.

Not for nothing are city councils around the world talking (dreaming) of "copenhagenizing" their cities by planning (hopefully) bike lanes and bike infrastructure.

For more info, stats and inspiration, see the Blog Categories links on the right column.

Sunrise Movement in Concerto, originally uploaded by [Zakkaliciousness].

The Copenhagen City Council produces a Bike Audit every couple of years in order to track bicycle usage in the city and plan more bike lanes and other infrastructure.

When they compare the 2006 Audit [Cykelregnskab 2006] with the one from 2004 it shows that the average amount of kilometres the average Copenhagener rides is unchanged. 1.2 million km each day.

Around 50% of cyclists ride up to 50 km each week. Then there is a group of 15% who ride more than 100 km each week.

The numbers for cyclists who ride up to 30 km each week show some interesting results:

34% ride up to 30 km a week to work.

68% ride up to 30 km a week on non-work related errands.

17% ride up to 30 km a week for recreation.

The latter means that 73% use their bikes for non-recreative usage. It is a means of transport, first and foremost, and not a conscious fitness-related vechicle.

That cycling is a good form of exercise, however, is the most important reason for riding for 19% of Copenhageners.

Another 38% mention excercise as one of the reasons.

In comparison, 51% of people say they ride because it is easiest and 45% say they ride because it is fastest.

In 2006, 36% of Copenhageners rode to work. The goal in the City's Cycle Policy is that 50% of the citizens will ride to work and educational institutions. The goal was previously 40% but has now been raised.

The City cites that improved infrastructure, including better controlled bike parking facilities are necessary if the magic 50% goal is to be reached.

Source: Copenhagen City Council's Cykelregnskab 2006

I love these groovy little street sweepers. They are designed to fit perfectly on the bike lanes of the city. In the winter they also have snowplough versions in the same size that keep the bike lanes clear.

Another example of how an established bicycle culture breeds the necessity of developing relevant gadgets to maintain them.

My Town, originally uploaded by [Zakkaliciousness] View of City Hall Square from the City Hall Tower. The blue pavement are bike lanes.

Last week the police in the capital had a campaign against marauding cylists. The good thing is that you hear about it in advance in the press but nevertheless 777 cyclists were stopped and fined for traffic violations.

A fine will set you back 250 Danish kroner. About €40. That's for each infraction. If you forget both front and back lights, for example, it's double up.

The 777 fines were divided up like this:

360 were colourblind. The majority of the fines were handed out to cyclists who ran the red light.

128 of them rode the wrong way on a one-way street.

70 were caught without bike lights on after dark - despite the fact that the sun sets at 22:00 and rises again at around 04:30.

71 were nicked for riding on the pavement [US: sidewalk]

26 for riding in the zebra crossing.

44 were in the wrong place on the lane when they turned.

It's worth mentioning that it's 777 tickets out of a few hundred thousands cyclists.

Source: Politiken [in Danish]

There is a tendency among many cyclists to interpret the law in a more casual manner. A few ride like morons but when you have half a million bikes on the roads each day, you expect some morons in the crowd.The Danish Cyclist Union has tried to get the police to use dialogue instead of fines and zero tolerance. To which the police commisioner responded, "We've tried dialogue, now it's time for fines".

Bike 1, originally uploaded by Annelogue.

This is a photo from another Copenhagen Flickrite - Annelogue.

For some reason, out of the blue (or red?) I remembered this shot yesterday - from ages and ages ago. I scoured my Favourites and was thrilled to find it again.

It's just as I remember it. A beautiful shot but all the more beautiful because it is completely scented with Copenhageniciousness. Be sure to click on the photo to see it it's full size - I don't know why photos appear like this when I blog them.

When you live in a country so completely saturated with bike culture it is often fun to see the details. Once your bike infrastructure is in place, it's time to get creative. Bike racks are, in many ways, merely functional devices for making a bike stand up while you're not on it. Kickstands are standard gear, of course, but when you have - in Copenhagen anyway - 36% of the population commuting by bike each day, you need solid racks to put the bikes in. In the hope - often vain - of maintaining order on the streets.

At busy train stations you'll often find double-decker bike parking. Obviously the lower level is first to be filled up but it's no difficult task to hoist your bike up to the next level.

Bike racks can be aesthetically-pleasing to the eye. Here the Danish tradition for cool, functional design comes into play.

A long line of bike racks outside a college. Just hang your handlebars on the hook and off you go.

In a narrow and ancient backyard, this is a creative space management solution. And no wet seats if it rains.

No wet seats if it rains here, either. Quaint little roofs cover the seat.

An elegant and functional little bike rack at the beach. It's winter and the rack eagerly awaits the summer hordes.

Even in a well-established bike culture there will be chaos. The sign reads: "Bicycle parking prohibited". :-)

The first step towards Copenhagenizing a city is, of course, investment in bike infrastructure. Trying to encourage people to ride their bikes but not providing them with the necessary infrastructure serves little purpose, in my eyes.

In countries that have yet to develop a bike culture the cyclists on the roads are primarily lycra-clad males from an inaccessible sub-culture. I'm sure there are people out there for whom this is a fetish, but for car drivers who harbour thoughts about riding their bikes to work or school it is a stumbling block. In their eyes riding their bike means having to integrate into a closed sub-culture of hard-core bike 'enthusiasts'. In the process they see that they will have to invest in 'fancy' gear and 'cool' bikes. Their old three speed city bike won't suffice.

In order to encourage more people to ride it is essential to make it look easy. You don't need lycra. You don't need fancy shoes, shorts, bikes. You only need two hands, two feet and two wheels.

Just look to the Danes and the Dutch or any other Northern European country for inspiration. You don't HAVE to look like the Lycra Boys. You have clothes in your closet. Wear them. Get sweaty easy? Ride slower.

This cool cat would surely look ridiculous in the lycra outfits you see on the streets of North American cities.

No need to look like a sports freak on your way to work.

Copenhageners in their natural environment and their natural clothes.

Copenhagenize Your City

Originally uploaded by [Zakkaliciousness]

I find a sight like this somehow pleasing to the eye. In city councils around the world they speak of "Copenhagenizing" their cities by building better infrastructure for bikes, including the all-important bike lanes.

Just read something interesting. How many kilometres do the citizens of various country ride on average each year?

Denmark: 958 km

Holland: 1019

UK: 81

USA/Canada: 70

Belgirum: 327

Germany: 300

Greece: 91

Spain: 24

France: 87

Ireland: 228

Italy: 168

Austria: 154

Portugal: 35

Finland: 282

Sweden: 300

Typical Copenhagen Bike Traffic Light.

On many of the busy roads and intersections bike traffic lights are provided for the bike lanes.

Like this one on Nordre Fasanvej in Frederiksberg.

Danish Bicycle Culture, originally uploaded by [Zakkaliciousness].

Fashionable Dane - complete with red boots - boarding the Intercity train to Copenhagen.

On local and regional trains you don't have to lift your bike up stairs, you just roll them on and place them in the bike racks on board. But this is the fast intercity train. Built for speed.

Here's a cool article about Danish [and Dutch] bike culture:

Building a Better Bike Lane

Bike-friendly cities in Europe are launching a new attack on car culture. Can the U.S. catch up?

By NANCY KEATES

COPENHAGEN — No one wears bike helmets here. They’re afraid they’ll mess up their hair. “I have a big head and I would look silly,” Mayor Klaus Bondam says.

People bike while pregnant, carrying two cups of coffee, smoking, eating bananas. At the airport, there are parking spaces for bikes. In the emergency room at Frederiksberg Hospital on weekends, half the biking accidents are from people riding drunk. Doctors say the drunk riders tend to run into poles. Flat, compact and temperate, the Netherlands and Denmark have long been havens for bikers. In Amsterdam, 40% of commuters get to work by bike. In Copenhagen, more than a third of workers pedal to their offices. But as concern about global warming intensifies — the European Union is already under emissions caps and tougher restrictions are expected — the two cities are leading a fresh assault on car culture. A major thrust is a host of aggressive new measures designed to shift bike commuting into higher gear, including increased prison time for bike thieves and the construction of new parking facilities that can hold up to 10,000 bikes.

The rest of Europe is paying close attention. Officials from London, Munich and Zurich (plus a handful from the U.S.) have visited Amsterdam’s transportation department for advice on developing bicycle-friendly infrastructure and policies. Norway aims to raise bicycle traffic to at least 8% of all travel by 2015 — double its current level — while Sweden hopes to move from 12% to 16% by 2010. This summer, Paris will put thousands of low-cost rental bikes throughout the city to cut traffic, reduce pollution and improve parking.

The city of Copenhagen plans to double its spending on biking infrastructure over the next three years, and Denmark is about to unveil a plan to increase spending on bike lanes on 2,000 kilometers, or 1,240 miles, of roads. Amsterdam is undertaking an ambitious capital-improvement program that includes building a 10,000-bike parking garage at the main train station — construction is expected to start by the end of next year. The city is also trying to boost public transportation usage, and plans to soon enforce stricter car-parking fines and increase parking fees to discourage people from driving.

Worried that immigrants might push car use up, both cities have started training programs to teach non-natives how to ride bikes and are stepping up bike training of children in schools. There are bike-only bridges under consideration and efforts to make intersections more rider-friendly by putting in special mirrors.

The policy goal is to have bicycle trips replace many short car trips, which account for 6% of total emissions from cars, according to a document adopted last month by the European Economic and Social Committee, an organization of transportation ministers from EU member countries. Another report published this year by the Dutch Cyclists’ Association found that if all trips shorter than 7.5 kilometers in the Netherlands currently made by car were by bicycle, the country would reduce its carbon-dioxide emissions by 2.4 million tons. That’s about one-eighth of the amount of emissions it would need to reduce to meet the Kyoto Protocol.

Officials from some American cities have made pilgrimages to Amsterdam. But in the U.S., bike commuters face more challenges, including strong opposition from some small businesses, car owners and parking-garage owners to any proposals to remove parking, shrink driving lanes or reduce speed limits. Some argue that limiting car usage would hurt business. “We haven’t made the tough decisions yet,” says Sam Adams, city commissioner of Portland, Ore., who visited Amsterdam in 2005. There has been some movement. Last month, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a proposal to add a congestion charge on cars and increase the number of bicycle paths in the city. It would also require commercial buildings to have indoor parking facilities for bikes.

Even in Amsterdam, not everyone is pro-biking. Higher-end shops have already moved out of the city center because of measures to decrease car traffic, says Geert-Pieter Wagenmakers, an adviser to Amsterdam’s Chamber of Commerce, and now shops in the outer ring of the city are vulnerable. Bikes parked all over the sidewalk are bad for business, he adds.

Still, the new measures in Amsterdam and Copenhagen add to an infrastructure that has already made biking an integral part of life. People haul groceries in saddle bags or on handlebars and tote their children in multiple bike seats. Companies have indoor bike parking, changing rooms and on-site bikes for employees to take to meetings. Subways have bike cars and ramps next to the stairs.

Riding a bike for some has more cachet than driving a Porsche. Dutch Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende sometimes rides to work, as do lawyers, CEOs (Lars Rebien Sorensen, chief executive of Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk, is famous for his on-bike persona) and members of parliament, often with empty children’s seats in back. Dutch Prince Maurits van Oranje is often seen riding around town. “It’s a good way to keep in touch with people on the streets,” says Tjeerd Herrema, deputy mayor of Amsterdam. Mr. Herrema’s car and driver still make the trip sometimes — to chauffeur his bag when he has too much work to carry.

Jolanda Engelhamp let her husband keep her car when they split up a few years ago because it was becoming too expensive to park. Now the 47-year-old takes her second-grade son to school on the back of her bike. (It’s a half-hour ride from home.) Outside the school in Amsterdam, harried moms drop off children, checking backpacks and coats; men in suits pull up, with children’s seats in back, steering while talking on their cellphones. It’s a typical drop-off scene, only without cars.

For Khilma van der Klugt, a 38-year-old bookkeeper, biking is more about health and convenience than concern for the environment. Her two older children ride their own bikes on the 25-minute commute to school while she ferries the four-year-old twins in a big box attached to the front of her bike. Biking gives her children exercise and fresh air in the morning, which helps them concentrate, she says. “It gets all their energy out.” She owns a car, but she only uses it when the weather is really bad or she’s feeling especially lazy.

Caroline Vonk, a 38-year-old government official, leaves home by bike at 8 a.m. and drops off her two children at a day-care center. By 8:15, she’s on her way to work, stopping to drop clothes at the dry cleaner or to buy some rolls for lunch. On the way home, she makes a quick stop at a shop, picks up the children and is home by 5:55. “It is a pleasant way to clear my head,” she says.

Teaching Newcomers

The programs for non-natives target those who view biking as a lower form of transportation than cars. “If they don’t start cycling it will hurt,” says Marjolein de Lange, who heads Amsterdam’s pro-bicycle union Fietsersbond and has worked with local councils to set up classes for immigrant women.

Bikes at the Amsterdam train station. Construction there begins soon on a 10,000-bike garage.

On a recent Sunday afternoon, 23 women — many in head-scarves — gathered at a recreational center north of Amsterdam to follow seven Fietsersbond volunteers to learn to navigate through traffic. The three-hour event cost €3 (about $4) and included practice weaving in and out of orange cones and over blocks of wood. It ended with all of the women gathering in a park for cake and lemonade.

Though she faltered at times, Rosie Soemer, a 36-year-old mother of two who came to the Netherlands from Suriname, was sold. “It is so much easier to go everywhere by bike,” she says. Learning to ride was her husband’s idea: He bought her a bicycle for her birthday a few months earlier and has been spending his lunch hour teaching her in a park. “It helps me if she can get around better,” says her husband, Sam Soemer. “And it’s safer than a car.”

Amsterdam and Copenhagen are generally safer for bikers than the U.S. because high car taxes and gasoline prices tend to keep sport-utility vehicles off the road. In Denmark, the tax for buying a new car is as high as 180%. Drivers must be over 18 to get a license, and the tests are so hard that most people fail the first few times. Both cities have worked to train truck drivers to look out for bikers when they turn right at intersections, and changed mirrors on vehicles and at traffic corners so they’re positioned for viewing cyclists.

As bike lanes become more crowded, new measures have been added to address bike safety. A recent survey found that people in Denmark felt less safe biking, though the risk of getting killed in a bike accident there has fallen by almost half. (The number of bicyclists killed fell to 31 in 2006 from 53 in 2004, and the number seriously injured dropped to 567 from 726 in that period.) According to one emergency room’s statistics, the primary reason for accidents is people being hit by car doors opening; second is cars making right-hand turns and hitting bikers at intersections; third is bike-on-bike crashes. Bike-riding police officers now routinely fine cyclists in Amsterdam who don’t have lights at night.

Parking for 10,000

Amsterdam is also working to improve the lack of parking. The city built five bike-parking garages over the past five years and plans a new one every year, including one with 10,000 spaces at the central railroad station. (While there’s room for 2,000 bikes now, there are often close to 4,000 bikes there.) But even garages aren’t enough. Bikers usually want to park right outside wherever they’re going — they don’t like parking and walking.

Combating theft is an important plank in developing a bike-friendly culture. In 2003, the city created the Amsterdam Bicycle Recovery Center, a large warehouse where illegally parked bikes are taken. (Its acronym in Dutch is AFAC.) Every bike that goes through AFAC is first checked against a list of stolen bikes. After three months, unclaimed models are registered, engraved with a serial number and sold to a second-hand shop. At any one time, the center has about 6,000 bikes neatly arranged by day of confiscation, out of an estimated total of 600,000 bikes in the city.

How AFAC will encourage bike riding in Amsterdam is a somewhat perverse logic, because it means some 200 bikes are confiscated by city officials a day compared to a handful before it existed. The thinking is that the more bikes that are confiscated, the more bikes can be registered and the better the government can trace stolen bikes. The less nervous people are that their bikes will be stolen, the more likely they are to ride. “Is your bike gone? Check AFAC first,” is the center’s slogan.

Remco Keyzer did just that on a recent Monday morning. The music teacher had parked his bike outside the central station before heading to a class and returned to find it gone. “I can be mad, but that really wouldn’t help me,” he says. Sometimes people ride away without paying the required fee. Bruno Brand, who helps people find their bikes at AFAC, says people get mad, but he explains it is the local police, not him, who confiscated the bike.

Within the past four years, the city increased the fine for buying or selling a bike in the street. Punishment for stealing a bike is now up to three months in jail.

Danish and Dutch officials say their countries might have been more congested if protests in the 1970s and 1980s had not sparked the impetus for building bicycle-lane networks. The arguments for more biking were mostly about health and congestion — only in the past year has the environment started to be a factor. Proponents of better infrastructure point to China as an example: In Beijing, where the economy has boomed, 30.3% of people commuted to work on bikes in 2005, down 8.2% from 2000, according to a survey by the Beijing Transportation Development Research Center and Beijing Municipal Committee of Communication.

Now, the Dansk Cyklist Forbund, the Danish Cyclist’s Federation, says that to make progress it can’t be too confrontational and must recognize that many bikers also have cars. “Our goal is the right means of transportation for the right trips,” says director Jens Loft Rasmussen.

In comparison, the rules of the American road can take some adjustment, as Cheryl AndristPlourde has found when she visits her parents in Columbus, Ohio. Last summer, the Amsterdam resident enrolled her 8-year-old daughter in a camp close to her parents’ house. The plan was for her daughter, who biked to school every day back home, to walk to camp. But her daughter whined about the 10-minute walk — all the other kids drove, she said — and the streets were too busy for her to bike. By the third day, Ms. AndristPlourde was driving her daughter to the camp.